Part 2: The Eightmile Lake Storage Proposal

This is the second of a four-part series regarding proposals to re-build a dam and increase water diversions from as many as seven lakes in the Enchantment Lakes region of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. Part 1 describes the genesis and functioning of the Icicle Work Group, the entity which is proposing the water projects. Part 3 examines the Upper Klonaqua Lake Pipeline proposal, and Part 4 examines the Alpine Lakes Automation-Storage project.

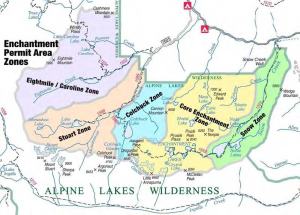

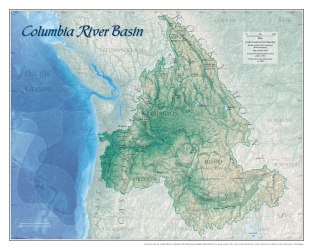

In a nutshell, the Department of Ecology’s Office of the Columbia River has funded Chelan County to investigate how to solve water problems in the Wenatchee River watershed. The primary focus of the effort is to increase water storage and diversions from seven lakes in the Enchantment Lakes region of the Alpines Lakes Wilderness.

This article discusses the proposal to rebuild a dam at Eightmile Lake and make more water available for the City of Leavenworth and other downstream uses.

The Eightmile Lake Restoration-Storage proposal evaluates the ability to increase water storage in Eightmile Lake by increasing the pool level and/or drawing the lake down further.

The original dam and control works for the lake have collapsed and current usable capacity is 1,375 acre-feet of water.

The Eightmile Lake Restoration Draft Appraisal Study (Nov. 2014) evaluates four options for increasing storage capacity: 2,000, 2,500 (2 options), and 3,500 acre-feet. All four options include re-building the dam to its original height, or higher, as well as drawing down Eightmile Lake pool below its current, semi-natural outlet. The Eightmile Lake proposal is based on assumptions about water rights and easements held by the Icicle and Peshastin Irrigation Districts (IPID), which actively manage four of the Alpine Lakes to serve water to about 7,000 acres of orchards and converted lands in the Wenatchee Valley.

IPID holds water rights dating from 1926 that allow the district to store water in and divert from the lakes. The Eightmile Lake water right was adjudicated in 1929 at 2500 acre-feet annual volume, and 25 cfs rate of diversion. However, the Eightmile dam collapsed at some point in the past and IPID has not used the full (artificial) storage capacity for many years. There are questions about relinquishment of water rights over and above what IPID needs and has used in the past. At a minimum, the Department of Ecology would have to issue water rights for new and increased uses.

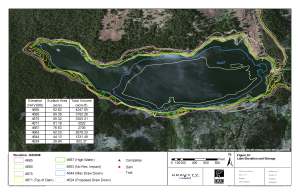

Eightmile Lake easements held by IPID are shown in blue (Aspect Consulting, Nov. 2014)

IPID holds easements that allow it to “store” water in several of the Alpine Lakes, although the scope of the easement for Eightmile Lake does not cover the entire lake. As described in a Review of Eight Mile Lake Storage Authority (Aspect Consulting, 3-5-14), IPID’s easements cover only a portion of the lake.

Any increase in storage capacity would require, at a minimum, U.S. Forest Service approvals. Section 4(d)(4) of the Wilderness Act of 1964 requires Presidential approval to establish and maintain reservoirs within wilderness areas.

The appraisal study hypothesizes that the easement language will allow and perhaps even require the Forest Service to approve an expansion of the reservoir: “In performing maintenance, repair, operation, modification, upgrading and replacement of [Eightmile Lake] facilities, [IPID] will not without prior written consent of the Forest Service, which consent shall not unreasonably be withheld, materially increase the size or scope of the facilities.”

Minimum and Maximum Inundation Levels for Eightmile Lake Restoration, Option 2 (Aspect Consulting, Nov. 2014)

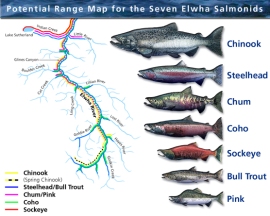

The Eightmile Lake proposal raises questions about the scope of impacts on riparian zones and wilderness surrounding the lake, including trails, campsites and other public amenities.

Eightmile Lake campsites and trails affected by lake elevation changes (from Forsgren Associates & Trout Unlimited, Icicle Irrigation District Instream Flow Options Analysis, July 2014)

Trout Unlimited has published a study evaluating increase in storage at Eightmile Lake to provide water to improve instream flows in Icicle Creek. That study includes a brief review of impacts to campsites and trails around the lake.

Eightmile Lake is one of the most popular trails and destinations in the Icicle Creek region of the Alpine Lake Wilderness, partly because of its easy accessibility. To date, however, the U.S. Forest Service has not provided a public position regarding proposals to expand or draw down Eightmile Lake.