This article was published in the January-February 2016 newsletter of the Washington Chapter of the American Water Resources Association. This version contains additional graphics and links to websites and documents.

Introduction

Washington AWRA members were introduced to the Icicle Creek work group process at the October 2015 dinner meeting and in a follow-up newsletter article. Chelan County Natural Resources Director Mike Kaputa presented on the costly (in both time and money) process that various government agencies, water users, tribes and environmental groups are undertaking with the ultimate goal of diverting more water out of the already over-appropriated Icicle Creek watershed. This article offers a different viewpoint of the Icicle Work Group’s process and goals.

The Icicle Work Group or IWG was established and funded by the Department of Ecology’s Office of the Columbia River (OCR) in December 2012 as a “collaborative process.” The IWG spent a year developing operating procedures based on consensus decision making, along with substantive goals that focused on environmental improvements and developing new water supply while adhering to state and federal laws.

Figure 1. Icicle Creek Subbasin Vicinity Map (Aspect Consulting Nov. 2012)

The IWG process targets an already over-appropriated water system. Icicle Creek drains a portion of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness area and discharges into the Wenatchee River near downtown Leavenworth. See Fig. 1. Four entities divert about 150 cfs from the Icicle upstream of the Leavenworth Fish Hatchery; two-thirds of that water is removed completely from the Icicle watershed to serve orchards in the Wenatchee Valley. Flows in some reaches of Icicle Creek are inadequate to support Endangered Species Act (ESA) listed bull trout and steelhead.

Before launching into particulars, a disclosure is appropriate. On behalf of the Center for Environmental Law & Policy, I was invited to serve on the IWG and did so (along with CELP colleagues) from the outset. At the first meeting of the IWG I voiced CELP’s objection to a central element of the IWG’s strategy: artificially increased water storage in the Enchantment Lakes, in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area. In February 2015, concerned that the public was not being apprised of IWG proposals, I published articles about the Alpine Lakes project at www.naiads.wordpress.com (“New Dams & Diversions in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness?”). In June, the IWG proposed to alter its decision process from consensus to majority vote, and adopt a rule that members must screen their opinions with the IWG before publicly airing them. CELP resigned from the IWG when these amended procedures were adopted in July 2015.

Background Conflicts

As with many water resource problems, there is a long back story to water management in Icicle Creek. Four different conflicts inform the work of the Icicle Work Group.

This first conflict begins with the building of Grand Coulee dam without fish passage, an egregious injustice to tribes and the public that has yet to be rectified. To partially mitigate, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1938 built the Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery. The Bureau still owns and funds the Hatchery, which is operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to produce chinook and coho salmon to meet federal trust obligations to the Confederated Colville Tribes and Yakama Nation. The Leavenworth Hatchery is a dilapidated facility suffering from decades of deferred maintenance, including relating to its water supply system. The Hatchery also blocks passage of ESA-listed steelhead and bull trout to the upper area of Icicle Creek – no small irony given that the USFWS is one of two federal agencies in charge of recovering endangered species.

In addition to its physical infrastructure problems, the Hatchery operates without proper permits and conditions. Wild Fish Conservancy and CELP have brought a number of lawsuits against the Hatchery, including three ongoing cases relating to Endangered Species Act, state 401 Certification, and federal Clean Water Act violations.

A second background issue involves a lawsuit between the City of Leavenworth and the Department of Ecology. In sum, in processing a water right change application in 1995, Ecology assigned an annual quantity to one of Leavenworth’s older water rights. Leavenworth did not appeal that quantification at the time, but recently sued Ecology to increase the annual quantity. A Chelan County judge ruled that Ecology’s 1995 quantification was a “tentative determination” that can be re-visited by the courts. The case is on hold in the Court of Appeals, a stay being obtained in 2013 based on Ecology’s promise to establish the Icicle Work Group and find more water for the City. The conflict boils down to 800 acre-feet annually, and Ecology is looking to provide that water via new appropriations out of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness area.

Figure 2. IPID Water Rights (Chelan County)

This relates to the third background issue – the water rights of Icicle Peshastin Irrigation District (IPID) (technically these are two districts that share a manager). IPID holds rights to store and take water from several of the Enchantment Lakes – these rights were grandfathered when the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area was established in 1976. See Fig. 2. IPID has installed various structures that control water flow from these lakes (“control” meaning that someone hikes up into the Wilderness in July to turn on the water, and then hikes back up in October to turn it off).

Figure 3. Because of the collapsed dam, Eightmile Lake has long been incapable of storing 2500 acre-feet of water. (Photo courtesy Karl Forsgaard)

When Ecology decided it would rather settle than fight the City’s lawsuit, it began to look at IPID’s wilderness water system as a source for the elusive 800 acre-feet. One of IPID’s rights is to store water at Eightmile Lake, where the dam structure collapsed so long ago no one remembers when it happened. See Fig. 3. If IPID could re-build the dam, and increase the water level of the lake, and if that extra water could be re-allocated to the City – well then, case dismissed and the Chelan County “tentative determination” order vacated.

A final issue involves the Wenatchee River instream flow rule, first adopted in 1983. In 2005, Ecology amended the rule to update instream flows and add reserves to support new water rights in the Wenatchee Valley. These reserves would impair the instream flow established by rule, and are based on “overriding considerations of the public interest” or OCPI, set forth in RCW 90.54.020(3)(a). Alert readers will recall that OCPI reserves are no longer valid following the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Swinomish Indian Tribal Community v. Department of Ecology. This effectively squelched the County’s efforts to obtain issuance of new water rights, and has led to (thus far unsuccessful) attempts in the Legislature to revive the Wenatchee reserves.

Figure 4. Actual streamflow in the Wenatchee River falls below the rule-based instream flow targets for most of the summer each year. The now invalid reserves would further deplete the Wenatchee River. (Graphic adapted from USGS data)

As an aside, the Wenatchee River and Icicle Creek routinely do not meet the Wenatchee rule’s instream flow targets during summer months. See Figure 4. This fact nicely illustrates the Supreme Court’s concerns about reserves impinging on the statutory mandate to preserve flows that support fish, wildlife, recreation and other instream values.

The Icicle Work Group Goals & Projects

With all this in mind, the Icicle Work Group was founded in 2012 as a consensus decision work group. The IWG adopted eight goals that seek both environmental improvements and new out-of-stream water allocations. In 2013, the OCR granted $885,000 to Chelan County to staff IWG with consultants and Ecology, WDFW and Chelan County employees. The IWG also pays $25,000 per year to IPID to fund its manager’s participation. Substantial legislative appropriations were made to support the IWG in the 2015-2017 biennium.

Figure 5. Icicle Work Group Instream Flow Technical Subcommittee recommendations for instream flow in Icicle Creek Reach 4 (adjacent to Leavenworth Fish Hatchery) (2014).

In 2014, the Work Group began to develop “metrics” to meet its goals. Identifying instream flow quantities necessary to meet fisheries needs in Icicle Creek, especially the de-watered reach adjacent to the Leavenworth Hatchery, was one consideration. IWG appointed a technical subcommittee of biologists, which recommended that 250 cfs was needed in order to maintain 100% of habitat for steelhead and bull trout life stages. See Figure 5.

Certain Work Group members however, found these quantities unacceptable. The 250 cfs number was “negotiated” down to 100 cfs in good years, and 60 cfs in drought years. This would make 80% or less of potential habitat available for ESA-listed fish, a problematic goal by state and federal standards. See “metrics” and Fig. 5. Some biologists have expressed doubt about the scientific foundations of this compromise, but when questions were raised, the IWG was informed that the decision could not be re-visited.

This process raises fundamental questions about the propriety of agency participation in “collaborative” groups. With consensus, all parties have veto. But IWG rules now require participants to support the metrics and project list. Agency commitment to outcomes in advance of public and environmental review is troubling, especially for regulatory agencies such as Ecology, Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, the U.S. Forest Service, and NOAA.

Also problematic is the approach to meeting these compromise flows. The current project list identifies only 22 cfs of “guaranteed” instream flow water – the rest would be interruptible. In a bad year, like the summer of 2015, Icicle Creek flows would plummet and temperatures skyrocket, while human users get the water they need.

Proposals to manipulate storage at Eightmile and other Enchantment Lakes, where IPID insists it has the “right” to expand its wilderness water system, are of great concern to the environmental community. The Alpine Lakes Wilderness is a crown jewel of the federal wilderness system and Eightmile Lake is one of its most popular trails. While the IWG has done some outreach, conservation community responses have had zero impact on development of the project list.

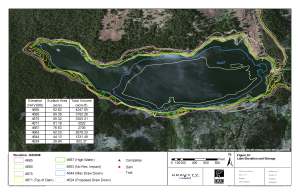

Figure 6. Eightmile Lake Easements do not cover the entirety of the lake. (Aspect Nov. 2014)

Beyond the failure to address public concerns, neither Ecology nor IPID has easements to flood wilderness surrounding the lakes, nor can the U.S. Forest Service give away public lands. See Fig. 6. Yet expanded storage in the Alpine Lakes is the IWG’s linchpin project – so important that it changed its rules in order to outvote CELP’s viewpoint. Indeed, CELP was directed to stop asking questions about these issues at IWG meetings.

The most expedient way to put 100 cfs into Icicle Creek is to move IPID’s diversion five miles downstream, from the Icicle-Snow Creek confluence to the Wenatchee River. However, IPID’s board voted to prohibit the IWG from considering this option. These actions raise interesting questions about the scope of water entitlements. Is a water user guaranteed their means of diversion, in this case miles of gravity-powered conveyance, that cause substantial environmental impacts?

Figure 7. No pear trees here. Former orchard lands in the Ski Hill area of Leavenworth have converted to residential, but are still afforded irrigation water duties for their lawns. (Photo: Naiads, June 2015)

Prior to resigning, CELP proposed that the project list should focus on rigorous conservation rather than new storage. An informal tour of the Leavenworth area in June 2015 produced a photo album of conservation opportunities, including IPID canal-side phreatophytes, orchard over-irrigation, and excessive residential lawn watering. See Fig. 7. Municipal demand has declined, and the City does not project significant need for future customers. Indeed, the City recently approved selling water to the Leavenworth Ski Hill for snowmaking in 2016. While the current IWG project list includes some conservation, IWG water users resist meaningful measures.

Upcoming IWG Process

Chelan County’s IWG website does not reveal when or how the IWG plans to move forward. The IWG was on track to begin SEPA scoping in autumn 2015, but when the legislature allocated IWG another $1-2 million for the 2015-2017 biennium, the process slowed. These funds will easily support the IWG battalion of consultants and agency staff for at least two more years.

State and federal coordination over environmental review (SEPA and NEPA) has also been difficult. One of the consequences of “integrated planning,” i.e., the lumping together of varied projects, is that affected agencies spend large amounts of publicly funded time to iron out procedures, turf conflicts, and other issues.

A few concluding observations.

First, as a matter of law and of biology, instream flows in Icicle Creek must be returned to more normative, historic levels. It is wrong to use legally required flows as a trading chit to obtain new out-of-stream water rights. This is particularly so given that the target sources are the Enchantment Lakes in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness.

Second, the IWG is not a collaborative process. The inability of the Work Group to contend with dissent – and its change in operating procedures to silence particular viewpoints – seriously undermines its legitimacy. Skepticism should be the response when the IWG extols the virtuosity of its group-think process.

Finally, public expenditures for the IWG and its projects should be re-evaluated. Ecology could purchase or condemn 800 acre feet of water for far less than the $64 million dollar tab that the IWG is about to drop on the public.

It is the responsibility of the Bureau of Reclamation and USFWS to bring Leavenworth Hatchery into compliance with state and federal laws. It is the duty of the four Icicle Creek water right holders to ensure they do not harm endangered salmonids, and to employ 21st century water efficiency practices. It is the mandate of the regulatory agencies to secure this compliance, not negotiate it away.

Ultimately, if an accurate picture is presented, the public will not pay for the sins and omissions of Icicle Creek diverters. Why are we spending millions to get that picture?

Water law is in the news with the famous “Hirst” decision being used to blockade the state capital budget. To understand how this roaring mouse could hold up a billion-dollar budget, several myths need dispelling. The bottom line is that proliferating wells are harming Washington’s public resources, especially aquatic habitat.

Water law is in the news with the famous “Hirst” decision being used to blockade the state capital budget. To understand how this roaring mouse could hold up a billion-dollar budget, several myths need dispelling. The bottom line is that proliferating wells are harming Washington’s public resources, especially aquatic habitat. First, a quick explanation of water law. Under state law, every drop of water belongs to the state, unless owned by the Tribes. To use water you must obtain a permit, called a water right, from the Department of Ecology. The major exception is for permit-exempt wells, i.e., wells that supply rural homes and businesses. The exception states that parties may use 5000 gallons per day of groundwater for household or commercial use, plus water for a half-acre of lawn or garden, plus water for livestock.

First, a quick explanation of water law. Under state law, every drop of water belongs to the state, unless owned by the Tribes. To use water you must obtain a permit, called a water right, from the Department of Ecology. The major exception is for permit-exempt wells, i.e., wells that supply rural homes and businesses. The exception states that parties may use 5000 gallons per day of groundwater for household or commercial use, plus water for a half-acre of lawn or garden, plus water for livestock. Based on this exception, hundreds of thousands of so-called “permit-exempt” wells have been drilled around the state. The Department of Ecology documented the increasing number of wells between 1970 and 2010 in an eye-popping set of maps.

Based on this exception, hundreds of thousands of so-called “permit-exempt” wells have been drilled around the state. The Department of Ecology documented the increasing number of wells between 1970 and 2010 in an eye-popping set of maps. Myth No. 2 is that we know how large the problem is. In fact, we have no idea how much water is used by these hundreds of thousands of unpermitted wells because, unlike city water systems, private well owners are not required to collect or report their usage. And that usage can be very large. For example, in 2011, the Washington Supreme Court ruled that permit-exempt wells may use unlimited quantities of water for livestock, including large feedlots. At issue in that case was a cattle feedlot that was using 600,000 gallons per day.

Myth No. 2 is that we know how large the problem is. In fact, we have no idea how much water is used by these hundreds of thousands of unpermitted wells because, unlike city water systems, private well owners are not required to collect or report their usage. And that usage can be very large. For example, in 2011, the Washington Supreme Court ruled that permit-exempt wells may use unlimited quantities of water for livestock, including large feedlots. At issue in that case was a cattle feedlot that was using 600,000 gallons per day. To suggest that permit-exempt wells involve only small quantities of water and have no impact is wrong. And because there is no permit up front, no metering, and no enforcement after the fact, permit-exempt well owners can use enormous quantities of water, and no one is the wiser.

To suggest that permit-exempt wells involve only small quantities of water and have no impact is wrong. And because there is no permit up front, no metering, and no enforcement after the fact, permit-exempt well owners can use enormous quantities of water, and no one is the wiser.